Could artificial intelligence one day replace humans in the field of journalism?

Ameera Fouad – Al-Ahram Weekly

What if one day you scrolled down to see an advertisement created by artificial intelligence (AI) and turned the page to read an opinion column written by AI accompanied by photographs taken by an AI photojournalist?

Then, you turned on the TV to watch the news bulletin presented by another AI anchor followed by a talk show anchored by a well-known AI figure welcoming a human being as a guest?

Of course, one cannot quite imagine all these AI media visualisation technologies actually happening in the world at the moment. However, Japan and China have their first robot news anchors in the shape of Erica, Qiu Hao and Xin Xiaomeng, and China has a robo-journalist website called Toutiao powered by AI.

In a groundbreaking seminar held at the Bibliotheca Alexandrina recently, AI and the future of the media were the topics of discussion, making many jaws drop. This advanced technology that has already boosted the world’s media platforms is not only seen in films today, but it has already been integrated into the real media industry.

“We already use AI in the media in minor forms like the use of algorithms, speech recognition, Google translate, cloud storage, and so on,” said Bassant Attia, head of the Media Department at the College of Language and Communication in Alexandria.

Attia was awarded a prize for best research paper at the 75th Media Conference at Cairo University this April, and in her paper, “The Future of AI and Media Professionals in Egypt”, she looks at how Egypt’s media professionals can integrate AI into their work in the light of the growth of machine learning worldwide.

Her paper enquires about the acceptance of this technology in Egypt and the Middle East and whether media professionals will be able to apply AI in their activities.

“Will we be able to watch someone like Qin Hao delivering the news to us,” as is already the case in China, Attia asked. “This will come true in the coming years, but I think we may be baffled by a robot reading the news,” she added.

“Here in Egypt we love human interaction. In a way we are more interested in the facial expressions than what is being said. We establish relationships with the TV anchors and radio announcers as a result,” Attia said, while at the same time arguing that media professionals in Egypt could benefit from AI.

“I can imagine a robot helping the anchors behind the scenes by gathering information, collecting data, and finding sources, but I cannot imagine robot anchors interacting well in a talk show, for example,” she added.

Journalist Nader Habib agreed, saying, “I can imagine AI in newsrooms organising data and finding sources. It can help journalists by establishing databases of sources with addresses and telephone numbers.”

“A journalist who wants information from a film or website could use AI to find it, accelerating the process of collecting data,” Habib added. “Robots cannot replace journalists, but they can help them. It is we, humans, who must find a way to establish relationships with the audience.”

Habib, deputy managing editor of Al-Ahram Weekly and speaking at the Alexandria seminar, said, “AI will enter journalism sooner or later. Robots have even proved themselves successful at writing articles.”

Habib was referring to the Xiaomingbot AI robot that is able to write news and sports articles. In fewer than two weeks, it was able to write 450 articles on the 2016 Olympics.

While a robot can write 450 articles in two weeks, any journalist cannot do this, he said. But though a robot can excel in terms of numbers, it is unlikely to be able to write the kind of quality articles that a human being can, he added.

“Do you think a robot can describe the scene when a football match is delayed because of a fan strike? It will not be able to analyse the causes of what happened,” Habib said.

DISAGREEMENT:

Such comments gave rise to disagreement between Attia and Habib to the surprise and interest of the audience, many of whom were hungry to hear more about the potential of AI.

AI can do everything but provide love or creativity, it was concluded. While many people are already using AI in its simplest forms, it cannot replace journalists or TV anchors. It cannot feel emotions, or observe, react and interact. “As a nation sometimes overpowered by emotions, AI will only make us feel detached,” Attia added.

Attia’s conclusion was similar to a view proposed by Kai-Fuee Lee, a computer scientist and AI professor, previously worked in Apple, Google and Microsoft. In a TED talk given in April 2018, Lee delivered a powerful speech about how AI can save humanity, but he added that “AI can do everything but one thing: love.”

“It is here to liberate us from routine jobs, and it is here to remind us what it is that makes us human,” Lee added, saying that he himself had realised late in life that technology had taken hours he should have spent with his father before he died as well as with his children and his mother.

Lee wants AI to take routine jobs from humans, allowing them to concentrate instead on creativity and art.

At the seminar, Attia also shed light on how AI can help in war and conflict zones. “Instead of sending a correspondent or reporter, a news organisation could send its AI correspondent who could do the same job and would prevent a human being from being killed or injured,” she said.

“AI might take photographs, send data, and even act in an objective way to both sides in a conflict.”

Many big news organisations and tech-savvy companies are using AI, often in the form of third-party vendors. The New York Times, for example, uses AI technology to look for patterns in campaign finance data. The Los Angeles Times has invented Quake Bot, AI responsible for detecting earthquakes within Los Angeles.

The US magazine Sports Illustrated uses AI to create info-graphics depicting players, games and match statistics. The news agency the Associated Press uses automated insights that can create content and generate stories about everything from public companies’ earnings reports to the outcomes of baseball games.

Toutiao (meaning today’s headlines) is a good example of how AI has already been used in the media. This is the first Chinese automated website, created in 2012, and it now has 200,000,000 visitors and has made $4 billion in profit.

“This website has everything you want. It registers your username and asks you questions to analyse your hobbies and interests. It thus tailors the news according to your interests and even your home address,” Habib said.

“If someone likes football, it will browse everything related to football in the area,” he added.

The site is based on tailoring content using natural language processing and computer vision, and it has community-based discussion forums to allow users to comment. Such mechanisms allow a robot to analyse the comments so that they can be used with the information and data on the website to generate content.

Although the website is state-of-the-art, it has drawn criticisms related to “spreading false information and fake stories and immoral values in advertisements,” Habib added.

He said that copyright violations like taking photographs and videos from other websites had been one of the main challenges. The site does not understand the values of the local culture, and this had been a problem in China, he added.

“Though Toutiao has claimed success as the first AI-powered personalised interface, it faces many challenges. The company was forced to hire more than 200 employees to control data entry, data correction and surveillance as a result,” he added. “If you are going to hire 200 employees to regulate AI, why not just hire 200 professional journalists instead,” he asked.

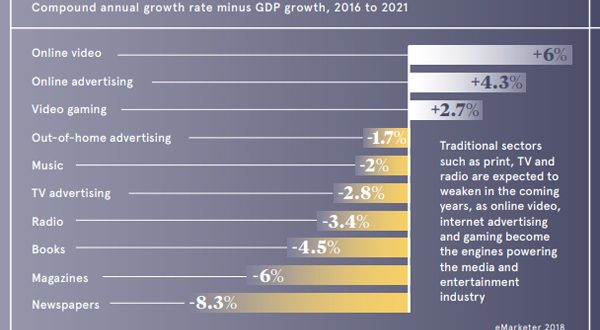

Today, many media professionals are faced with a choice between being part of the fourth industrial revolution of AI and being left behind. Since the latter is not an option, they will have to find ways to invest in AI technologies.

According to a recent report by Pricewaterhouse Coopers, a professional services network, it is expected that the Middle East will accrue two per cent of the total global benefits of AI by 2030, or the equivalent of $320 billion. The report says that if governments can push for innovation and creativity across AI sectors including the media, the impact on economic growth could be much larger.

One pioneering AI media platform in Egypt is Sarmady, created in 2001. This is the first fully-fledged digital media company that has a mission to create “infinite digital”. The company, owned by Vodafone Egypt since 2008, is a creator of digital content whose services range from news, sports and entertainment to city guides and directory services.

It reaches clients and users via the web, mobile-Internet, mobile applications, SMS and voice applications. It has recently launched an Arabic news website called Mujaz.me for mobile web development.

The media industry has seen much progress over the past 20 years, including traditional media convergence and participatory media. Now we are on the verge of another revolution that will shake the industry. If traditional news organisations have not introduced AI or machine learning by 2030, they might not be able to integrate into the fast-developing new industry.